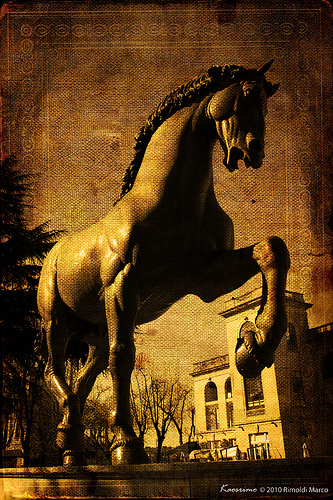

61. Sentirsi piccoli piccoli di fronte al cavallo di bronzo più grande del mondo

61. Feeling very small in front of the world’s largest bronze horse

| Durante la visita all’Ippodromo del Galoppo, non potrete fare a meno di imbattervi nell’immenso cavallo di bronzo. La storia di questa statua è molto particolare. Nel 1482 Ludovico il Moro Duca di Milano, propose a Leonardo di costruire la più grande statua equestre del mondo: un monumento a suo padre Francesco, duca dal 1452 al 1466 (anno della sua morte), che era anche il fondatore della casata Sforza. L’impresa era colossale, non solo per le dimensioni previste della statua, ma anche per l’intento di scolpire un cavallo nell’atto di impennarsi ed abbattersi sul nemico. Leonardo sapeva perfettamente che la qualità del cavallo era molto importante per sottolineare l’importanza del personaggio e quindi studiò a fondo, nelle scuderie ducali, tutti i dettagli anatomici dell’animale, realizzando disegni preparatori usando come modelli alcuni cavalli già famosi per la loro bellezza. I disegni ritraevano proprio le parti anatomiche più belle di ciascun cavallo, con l’intenzione di farne una specie di “montaggio” per ottenere il cavallo ideale. La lentezza dei lavori, interrotti anche per la preparazione delle nozze di Anna Maria Sforza e Alfonso I d’Este (programmate nel 1490 e rimandate al 1491) e per quelle di Ludovico il Moro e Beatrice d’Este (1494), dovettero preoccupare il Moro, il quale spazientito provò a rivolgersi ad altri scultori, iniziando a diffidare di Leonardo. Nessuno però accolse la sfida. |

During the visit to the Gallop Hippodrome, you cannot see the immense bronze horse staue. In 1482 the Duke of Milan Ludovico il Moro proposed to Leonardo to build the largest equestrian statue in the world, a monument to his father Francesco. The undertaking was enormous, not only for the expected size of the statue, but also in the intent of sculpting the horse in the rear up and fall on the enemy act. Leonardo knew perfectly that the quality of the horse was very important to emphasize the importance of the figure, so he studied in depth, in the ducal stables, all the anatomical details of the animal, making preparatory drawings, he used as models some horses famous for their beauty . The drawings depicting the most beautiful parts of each horse, with the intention of making a kind of “assembly” to get the perfect horse.

The slow pace of work, interrupted for the preparation of the marriage of Anna Maria Sforza and Alfonso d’Este and for those of Ludovico il Moro and Beatrice d’Este (1494), worry the More, who impatiently tried to find another sculptor to substitute Leonardo, but no one accepted the challenge. |

|

Nel frattempo il progetto era cambiato. Il cavallo rampante probabilmente creava eccessivi problemi di equilibratura. Inoltre il monumento venne ripensato di forme colossali, fino a quattro volte più grande del naturale. Un simile progetto, quindi, rese necessario ridisegnare il cavallo al passo, ed entro il maggio 1491 l’artista aveva approntato un nuovo modello in creta, in occasione del matrimonio della nipote del duca con l’imperatore d’Austria. Leonardo, con questo monumento, voleva realizzare un’opera che oscurasse tutte le precedenti statue equestri. A Leonardo interessava, in realtà, più il cavallo che il cavaliere; il suo cavallo doveva essere il più grande di tutti, superare i 7 metri di altezza, una sfida mai tentata prima. Proprio per questo Leonardo riempì fogli e fogli di schizzi di anatomia, studiando muscolatura e proporzioni del cavallo e passando moltissimo tempo a progettare e calcolare quest’opera gigantesca che, per la sua fusione, avrebbe richiesto ben 100 tonnellate di bronzo. Il colossale modello in creta venne esposto pubblicamente, nel 1493, suscitando l’ammirazione generale. A quel punto l’opera doveva solo essere ricoperta di uno spesso strato di cera e quindi della “tonaca” in terracotta, in cui versare il metallo fuso. Tutto era pronto per realizzare davvero l’opera, ma le 100 tonnellate di bronzo necessarie alla realizzazione del monumento non erano più disponibili, essendo state utilizzate per realizzare dei cannoni utili alla difesa del ducato d’Este dall’invasione dei francesi di Luigi XII. Leonardo abbandonò il progetto e partì da Milano.

|

Meanwhile, the project had changed. The prancing horse probably created excessive balancing problems. Moreover, the monument was redesigned four times larger than natural. A similar project, therefore, required to redesign the horse at a walk, by May 1491 the artist had developed a new model in clay, for the marriage of the grandson of the duke with the Emperor of Austria.

Leonardo, with this monument, wanted to overshadows all the previous equestrian statues. Leonardo was more interested to the horse itself than to his rider. His horse had to be the greatest of all, more than 7 feet high, a challenge never attempted before. Precisely for this Leonardo filled sheets and sheets of sketches of anatomy, studying muscles and proportions of the horse and spent a lot of time to design and calculate this giant work. Its merger would have required as much as 100 tons of bronze. The colossal clay model was exhibited publicly in 1493, arousing admiration. At that point the work had only to be covered with a thick layer of wax and then of a terracotta “habit”, in which pour the molten metal. Everything was really ready to make the work, but the 100 tons of bronze needed for the construction of the monument were no longer available, having been used in the manufacture of the guns use in the defense of the duchy of Este from the invasion of Louis XII’s French Army. Leonardo abandoned the project and set out from Milan. |

|

Nel 1977 Charles Dent, un pilota americano collezionista d’arte e amante della scultura, si entusiasmò all’idea di realizzare dopo cinque secoli il sogno di Leonardo. Mise in piedi l’organizzazione e riuscì, dopo più di quindici anni di impregno, a trovare i fondi: il costo del cavallo, alla fine, arrivò a quasi 2,5 milioni di dollari. L’uomo comunque non riuscìì a vedere realizzato il proprio sogno, morendo nel 1994, prima che l’impresa fosse completata. Alla morte di Dent il progetto stava per essere abbandonato, quando Frederik Meijer, proprietario di una catena di supermercati nel Michigan, si offrì di finanziare il progetto, purché si facessero due cavalli: uno per Milano e l’altro per i Meijer Gardens, un parco naturale e artistico a Grand Rapids (Michigan) Il progetto è andato avanti fra numerose difficoltà e alla fine la direzione dei lavori è stata data alla scultrice Nina Akamu che ha finalmente condotto in porto l’impresa. Le sette parti in cui il cavallo era stato fuso arrivarono nel luglio del 1999 a Milano dove vennero saldate insieme. Dopo qualche discussione il cavallo fu posto nel settembre 1999 all’ingresso dell’ippodromo di San Siro. |

In 1977, Charles Dent began work to complete the unfinished sculpture in Allentown, PA. His efforts to set up the organization to finance the project, however, proved a difficult task that required more than 15 years. The cost of the horse came to nearly US$2.5 million, but Charles Dent died of Lou Gehrig’s disease on Christmas day of 1994, he left his private art collection to LDVHI(Leonardo da Vinci’s Horse, Inc.), and its sale brought more than $1 million to the fund. In 1988, LDVHI enlisted sculptor/painter Garth Herrick to begin part-time work on the horse. By 1997, Tallix Art Foundry, in Beacon, New York, the company contracted by LDVHI to cast the horse, had suggested bringing Nina Akamu, a talented animal sculptor, on board to attempt to correct the anatomical faults of the Dent-Herrick horse. After several months of trying, Akamu determined that the original model could not be salvaged and concluded that a completely new sculpture needed to be executed. During the 17 years that Leonardo had worked on the horse, he had made numerous small sketches of horses to help illustrate his notes about the complex procedures for molding and casting the horse. But his notes were far from systematic, and none of the sketches points to the final position of the horse. The absence of a single definitive drawing of the statue left the 20th-century artist some latitude for interpretation. Akamu researched multiple information sources to gain insight into the original sculptor’s intentions. She studied both Leonardo’s notes and drawings of the horse and those of other projects he was working on. She reviewed his thoughts on anatomy, painting, sculpture and natural phenomena. Her research expanded to include the teachers who had influenced Leonardo. Akamu also studied Iberian horse breeds, such as the Andalusian, which were favored by the Sforza stables in the late 15th century. In September 1999, the 24 feet (about 7.3 metres) tall horse was placed at the hippodrome de San Siro in Milan.

Two copies of the horse were constructed, at least one with the money of billionaire Frederik Meijer. This second sculpture is now visible in the Frederik Meijer Gardens & Sculpture Park, a natural park in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Another copy of the horse has been placed in downtown Allentown, PA’s Community Art Park adjacent to the Baum School of Art in honor of Charles Dent. It is smaller (twelve feet) bronze replica of the two larger statues. A fourth (eight feet) bronze replica has been installed on 15th September 2001 in the Piazza della Libertà, Vinci, Italy – the birth town of Leonardo. |

Immagini © 2010 Rimoldi Marco L’intero album con le immagini di questo post è disponibile su flickr.  Alcune parti del testo derivano da una riproduzione o una modifica del testo delle rispettive voci di Wikipedia, pertanto l’intero testo è disponibile secondo la Licenza Creative Commons. Alcune parti del testo derivano da una riproduzione o una modifica del testo delle rispettive voci di Wikipedia, pertanto l’intero testo è disponibile secondo la Licenza Creative Commons. |

Pictures © 2010 Rimoldi Marco The complete album is available on flickr.

Some parts of the text are a reproduction or a text editing from the respective Wikipedia article, so the entire text is available under the Creative Commons License. Some parts of the text are a reproduction or a text editing from the respective Wikipedia article, so the entire text is available under the Creative Commons License. |